Consultant Spotlight: Sunday de Joux, Dental Anthropology Expert

Dental anthropology is a subset of bioarchaeology and is the analysis of variations in the morphology and dimensions of human teeth, as well as micro and molecular analysis of dental components.

We recently sat down with Graduate Heritage Consultant Sunday – our resident expert on teeth – to discuss the significance of the discipline in cultural heritage assessments.

How did your interest in working with teeth develop, and what inspired you to specialise in dental anthropology?

All four of the traditional fields of anthropology continue to fascinate me, but my university only offered three! I took papers in social anthropology, archaeology, and bioarchaeology all through undergrad and honours year (vowing to one day to study linguistic anthropology to round out the whole set).

I technically started specialising in bioarch in my honours year; my dissertation focused on a pathological analysis of dental remains from a rural colonial town in Aotearoa New Zealand. I learnt a lot about what teeth can tell us about a person’s life, the methods of assessing dental remains, and about their unique value and opportunity as an archaeological resource. My interest was further cemented (teeth pun intended) during my master’s, which was a very involved project focused entirely on dental anthropology.

Teeth can have various cultural, historical, and scientific significance. In your work, how do you approach the multifaceted aspects of teeth, and what methodologies or techniques do you employ?

Huge question! Like almost everything with the human body, the data that can be collected from dental remains is often much more subjective than you might assume. A common mistake is to assume that metric data collected from skeletal remains correlates to definitive truths about the people whose remains you are studying. One of the strengths of bioarchaeology is to take this ‘hard data’ and to analyse it with an intersectional, nuanced approach to learn about the health and society of ancient populations!

My master’s project was a great example of this relationship. My aim was to investigate the relationship between increasing social inequality and health outcomes within disadvantaged populations by assessing an ancient Chinese skeletal assemblage. The project delved into systemic stress caused by socially driven dietary differences, inequality of access to adequate medical attention, and the physical manifestation of psychological trauma. It also involved a thorough history of the regional Eastern Zhou, a sociological section on gender in ancient China, and of course, all the relevant contemporary bioarchaeological research. A whole bunch of different skills from a whole bunch of different fields that wove into one story!

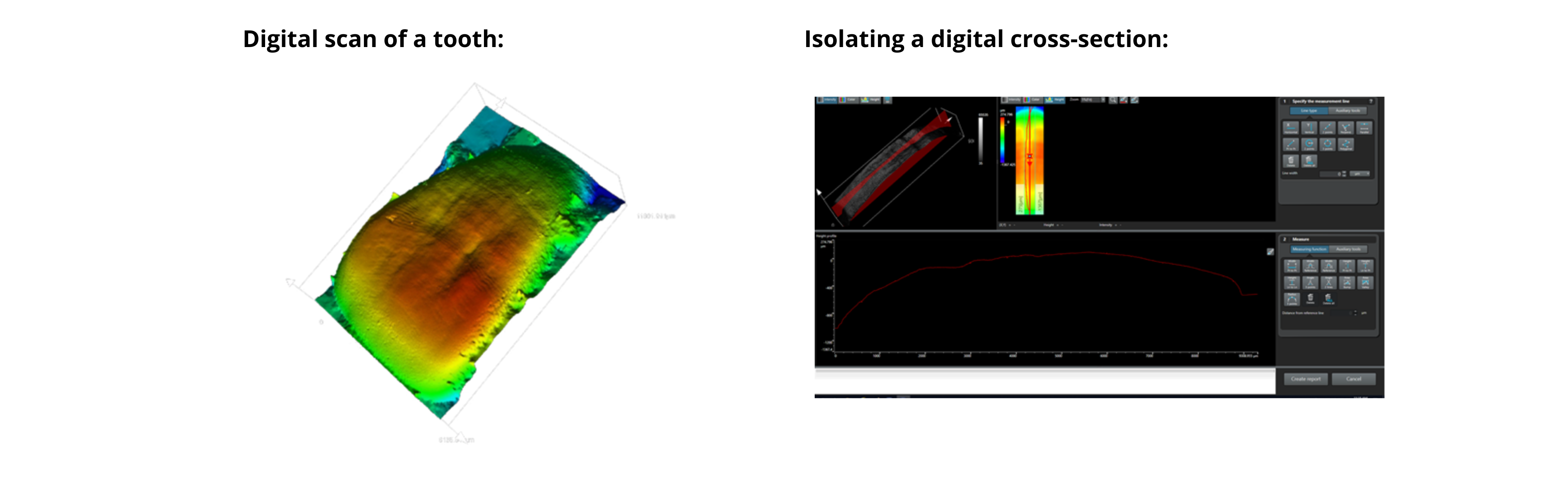

Bullet pointing the key techniques I’ve used rather than getting bogged down in technobabble:

- The new micro-polynomial method of identifying linear enamel hypoplasia, plus the classic macro and micrometric methods

- Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) theory to analyse my results

- General pathological assessments (looking for evidence of dental diseases)

- Multifactorial analysis, all bioarch needs multiple data sources for a proper analysis

- Historical, methodological, and scientific research

- Lab work and field assessments galore!

How do teeth play a role in cultural heritage assessments? And when or why might your specialty be required?

As enamel is largely mineral content, both human and non-human teeth are generally great survivors in the archaeological record. If skeletal remains are present at an archaeological site, there’s a very good chance that teeth will be among them. Depending on the state of preservation teeth are sometimes the only surviving bones. Being able to identify if those teeth are human or non-human is extremely important, especially since many species have teeth that can look a lot like a human’s – notoriously, skeletonised pig remains have given many a scare upon discovery due to their striking resemblance to human anatomy.

Archaeological animal teeth could indicate a range of site types, such as middens, butchery sites, animal husbandry, or natural deposition. In contrast, the presence of human remains of any description is cause for immediate action onsite. The police must be alerted to determine if the site is archaeological or forensic. Naturally, the presence of any human remains within an archaeological site is charged with a lot of cultural weight and importance, especially within the historical and cultural context of New South Wales.

The appropriate modes of working with human archaeological remains varies drastically by culture, overlaid and often exacerbated by the history of colonialism. Human remains could indicate a traditional Aboriginal burial, a cemetery, a massacre site, or an isolated accident, among many other types of sites. Making deliberate and careful steps to work respectfully alongside the relevant cultural groups is extremely important, and being able to provide confident expertise is equally so.

Can you share a specific project or area of work where your expertise in working with teeth played a significant role? What were the key challenges and discoveries in that project?

The discovery of unexpected bone put one recent site on hold in the Wollongong area last year. After being told that someone would need to travel down to confirm if the bone was human or animal, I was the first to put my hand up! Solid archaeozoological skills are essential to being able to ID bone correctly, and depending on the state of preservation and assemblage, bones can be IDed to a specific species, element, and even side. I was able to determine that the bone was decidedly sheep!

As discussed above, bone is a material with huge cultural weight that can be extremely emotionally evocative. Upon discovery there’s often a pervasive sense of unease in the limbo before the context of the bone has been determined. In the case above, it was incredibly important to me that I was able to reassure everyone on site that the bone did not represent an impacted burial. No archaeological material is ever completely neutral, but in many ways bone is uniquely charged.

For aspiring heritage consultants interested in specialising in teeth artifacts, what advice would you give regarding skill development and career possibilities?

For the field of bioarchaeology: stay open minded, keep reading, and be wary of assumptions!

More practically, if you ever have a chance to look at a comparative reference collection, that’s probably the best way to see the differences in tooth type and species morphology! If that isn’t accessible, read books with pictures, watch videos and lectures posted by universities, and attend workshops when offered. Biological archaeology and archaeozoology are definitely fields where experience with physical material is the best way to learn :~)